The Woods Institute is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability

Hurricane Florence: The science behind the storm

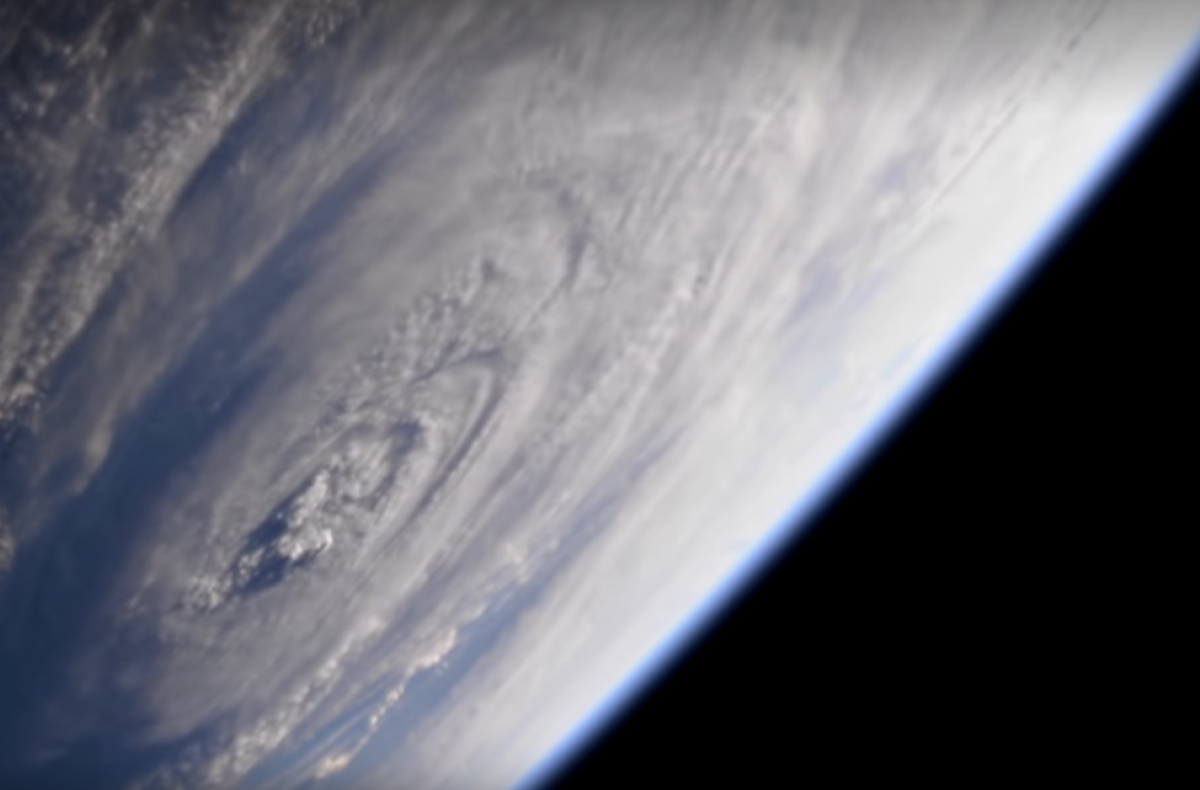

Hurricane Florence as see from space

NASA

Sep 14, 2018

By:

Hurricane Florence began pummeling North Carolina with drenching rains, powerful winds, and the threat of catastrophic flooding after making landfall in the early hours of Friday, September 14. Moving inland at a dangerous crawl, the storm was forecast to dump up to 40 inches of rain in some parts of the Carolina coast and drive ocean water into storm surges taller than 10 feet(link is external) if it struck at high tide.

By Sunday, September 16, the storm had slowed to a tropical depression, but rain continued to fall and floodwaters continued to rise(link is external) across the region. The death toll had reached at least 17(link is external), and officials warned of sustained risk from landslides(link is external), flash floods, and prolonged river flooding(link is external).

When Hurricane Florence made landfall, it was the largest of four big storms brewing in the Atlantic. “This is an extraordinarily active month - not just for the Atlantic, which we tend to think of because of its concentration of American cities, ports and industry, but also the Pacific,” said atmospheric scientist Morgan O’Neill, a professor of Earth system science in the Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). Super Typhoon Mangkhut(link is external) has barreled through Southeast Asia, killing dozens in the Philippines and slamming Hong Kong before reaching mainland China on September 16. Japan, meanwhile, has only begun to recover(link is external) from Typhoon Jebi, the strongest typhoon to make landfall there in 25 years.

O’Neill explains how simultaneous hurricanes can be connected, why Florence followed an unusual track through the Atlantic, and why flash floods are a particularly grave threat with this storm.

How does this season's activity compare to a normal year?

MORGAN O’NEILL: Early September is the climatologically most active period for the Atlantic Basin, which includes the Atlantic as well as the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. This year is so far much more active than an average hurricane season.

Storms get named once their peak wind speed reaches 39 mph or greater, and this is the first time in a decade(link is external) that the Atlantic has four simultaneous “named” storms: Florence, Helene, Isaac(link is external) and Joyce.

The Pacific is similarly expected to be active from late-August to early-September. This year it has been not just active, but brutal. Typhoon Jebi made landfall in Japan last week, causing widespread, serious damage, and Typhoon Mangkhut is driving evacuations in the Philippines before its anticipated landfall at speeds equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane. The Pacific typically has larger, stronger, better organized and more deadly storms, and the western Pacific is the most active region for tropical cyclones on the planet.

Does one hurricane beget or fuel another?

O’NEILL: The short answer is, we don’t know. We do know that hurricanes can have both mitigating and compounding impacts on nearby or near-future hurricanes. Exactly how one hurricane influences another depends on factors ranging from the amount of upper-ocean mixing, how the steering winds of the two storms interact, and how air flows out of the hurricanes into the upper atmosphere.

Understanding these varying effects in concert is a pretty exciting, open area of inquiry. Numerical modeling is a very economical way to study this, since we can turn on and off different levels of complexity in the “laboratory” of our numerical experiments. However, continued observations by satellite, plane, buoys, and air and sea drones are essential for ultimately testing whatever idealized mechanisms we find in our simulations.

No tropical storm or hurricane has been recorded within 100 miles of where Florence was late last week and still made a U.S. landfall. Why is Hurricane Florence’s track so unusual?

O'NEILL: It’s very unusual for a hurricane to move so consistently westward while at such a high latitude. Typically storms this poleward interact with the jet stream rather quickly and are sheared and consumed by midlatitude high- and low-pressure systems, losing their tropical characteristics and moving northeastward. However, this week the jet stream is quite northward of the Carolinas, with little influence on Florence, and Florence instead is being largely steered by the nearby Bermuda High – a subtropical area of high pressure in the Atlantic. It’s an unusual but by no means black swan kind of event.

What is it about Florence and the Carolinas that could make for a particularly dangerous combination, and how does that compare to the damage caused by recent storms of similar intensity?

O’NEILL: In some ways this hurricane has a lot in common with Hurricane Harvey from last year. It is expected to stall right upon landfall, and sit in the same general area for a few days while dropping a catastrophic amount of rainfall, in addition to the deadly storm surge expected from a hurricane of this size. And this is what kills people — water, not wind.

What Florence does not have in common with Harvey is the topography of the landfall location. The Carolinas have substantial hills and valleys that will concentrate tens of inches of rain into narrow, devastating flash floods. In Houston, the flat topography meant that everyone flooded. With Florence, people may not anticipate or appreciate potentially historic flash flooding.

This is extremely dangerous not just because of flash floods' ferocity but the difficult problem of forecasting such spontaneous, hyper-local events with any amount of actionable lead time. Additionally, the storm surge – warm, salty ocean water that is pushed up onto the shore and inland from the winds and forward motion of the storm - will slow or block the ability of rivers overflowing with potentially record-breaking rainfall to drain into the ocean, out of populated areas.

What does all of this mean in terms of climate? What do scientists know about the connection between climate change and storms like Hurricane Florence?

Scientists are slowly converging(link is external) on an at-least partial understanding: yes, climate change fuels stronger storms and makes those storms more likely. It doesn’t necessarily make all storms more likely, and indeed the total frequency may go down a bit or stay roughly the same, but the storms on the very strong end of the spectrum are increasingly likely to occur. This is in part because the heat stored in the upper tropical ocean, as measured by sea surface temperatures, is the primary fuel source for hurricanes, and it is increasing.

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation is also at work: a warmer atmosphere contains more water vapor, which provides a more hospitable environment for the formation and intensification of tropical cyclones. Stronger storms can push more sea water as storm surge onto land, and this now occurs on a higher baseline due to sea level rise. So even though it’s extremely difficult to say which individual storm is impacted in what way by climate change, we are certainly tipping the scale in favor of more damaging storms by virtue of changing they environment in which they occur.

Contact Information

Christine H. Black

Associate Director, Communications

650.725.8240

ChristineBlack@stanford.edu(link sends e-mail)

Devon Ryan

Communications Manager

650.497.0444

devonr@stanford.edu(link sends e-mail)

Rob Jordan

Editor / Senior Writer

650.721.1881

rjordan@stanford.edu(link sends e-mail)