The Woods Institute is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability

Environmental Photography Exhibit at Stanford

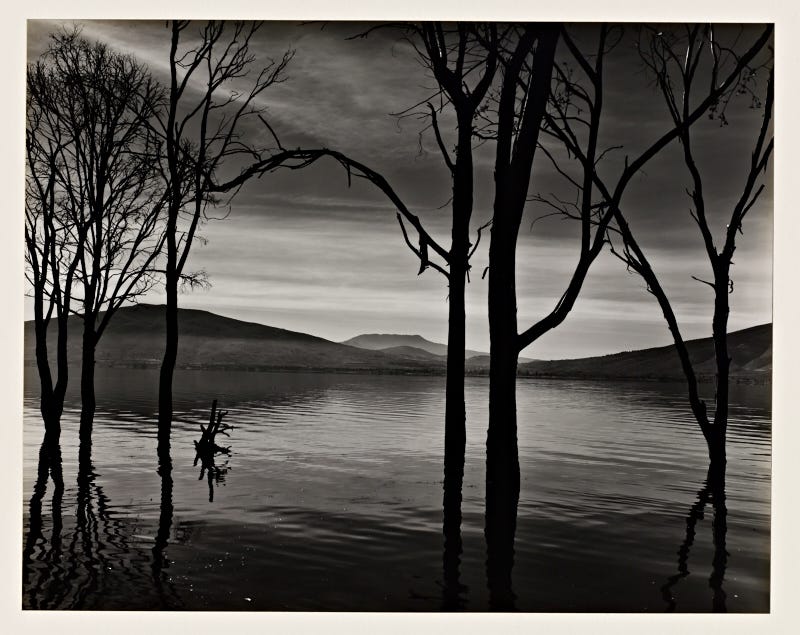

Lakescape, 1973. Gelatin silver print on board.

Brett Weston

Sep 15, 2017

By:

I admire those pictures most that acknowledge our predicament without causing us to lose heart, just as I am most touched by those places where damage and grace are inextricably entangled. Frank Gohlke

There is currently an exhibit on view, in a tiny room on the second floor of the Cantor Arts Center, that you should go and see. There is some guilt in writing these words, because it is only there until September 18th, which at the time of this writing is 5 days away.

The exhibit, entitled Environmental Exposure, focuses on landscape and environment photography in the 1970s, a period of awakening for environmentalists but also a remarkable time of renewal in the photographic approach to landscape. On June 1, 2017, at the exhibition opening, curator Michael Metzger delivered a brief lecture exploring the various themes seen throughout the 23 works on view. He emphasized that photographs are not merely important for what they depict, but for what they perform. Every photograph, he asked the audience to understand, is not just a representation, but also and perhaps more importantly an intervention.

Earthrise, taken by Apollo 8 crewmember Bill Anders on December 24, 1968. Widely credited as the most important environmental photograph of all time. (Not part of the exhibition)

A prime example is Earthrise, the famous photo of Earth taken from Apollo 8 in 1968. It is crucial not only because it is the first color photograph of Earth from space, but also and more importantly because it sparked and materialized a generalized public awareness of the “Earth island” idea — the fact that we are all in the same tiny boat floating in an ocean of dark inhospitable matter (corollary: we better take care of our boat, lest we sink with it).

Half Dome, Yosemite Valley, California, circa 1865, by Carleton Watkins. Photographs like this one were largely credited with moving public officials to establish national parks as sanctuaries for preserving these kinds of views for future generations. (Not part of the exhibition)

Some of the earliest photographs ever taken are landscape photographs — for the simple reason that shutter times were slow and landscapes have the good sense of not moving too much. From the very beginning, though, Metzger showed how two ways of seeing nature reflected two ways of thinking about it in relation to human beings: it could either be perceived as an intrinsically valuable good, a sanctuary, as per John Muir’s thought; or it could be seen as a resource and a backdrop for human recreation, reflecting more of how Gifford Pinchot perceived its value. In the end, Pinchot’s vision is the one that prevailed: the National Parks system was created with the mindset of preserving some limited enclaves of untouched pristine nature for the enjoyment and benefit of the vacationing masses.

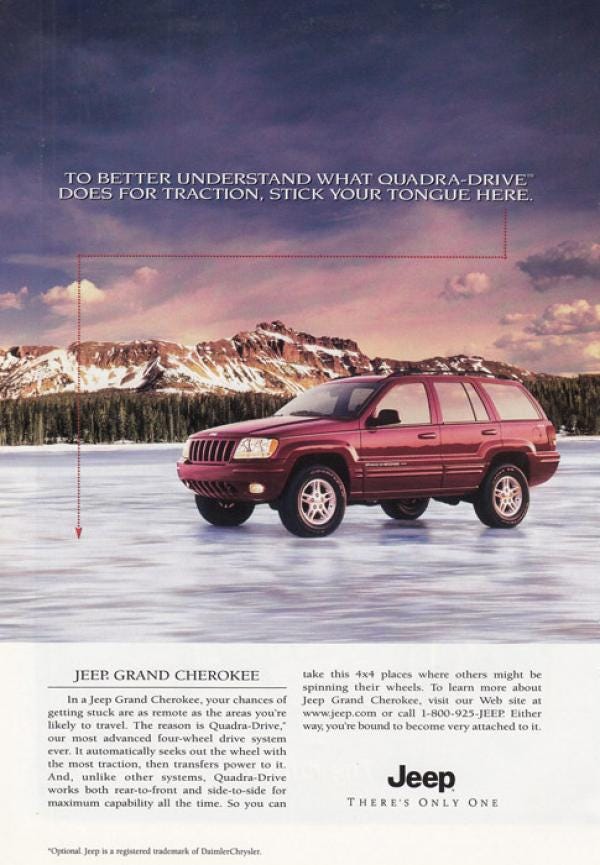

Photography became the art of showing nature as a beautiful spectacle used to shield Americans from the actual devastating impacts of unfettered industrial activity and wasteful consumerism on ecosystem life. This type of imagery was especially pervasive in advertising; strangely enough it still persists, despite the changing trends in nature photography that this exhibit makes clear. Indeed, nature in advertising is still predominantly depicted as the nostalgic, untouched mythical backdrop to our activity — most ironically, that of driving a highly polluting car.

Jeep Grand Cherokee print ad, 1999 (not on view).

This all changed in the 1970s, a decade of eye-opening and reckoning that photographers in the New Topographics movement (including Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz,Bernd and Hilla Becher, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, and Stephen Shore) played a major role in. After the 1962 publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which is widely credited with marking the beginning of the era of modern environmentalism, photographers turned away from the smokescreen of picture-perfect images and started realistically depicting the way humans inhabit nature, exposing (pun intended) the complex and sometimes unfortunate couplings between the two.

Brett Weston (U.S.A., 1911–1993), Lakescape, 1973. Gelatin silver print on board.

The New Topographics artists deliberately showed scenes where the natural landscape had been taken over by seemingly pointless human activity, like huge swaths of highway or strip malls. These pictures underline, rather than hide, the vulnerability of nature to man. They expose the rabid expansion of private property and the ruthless exploitation of resources, with no regard for environmental damage. At the same time, they no longer portray nature as an idyllic refuge or oasis which is somehow disconnected from human life. These photographers attempted, as best they could, to shock viewers out of passively contemplating pictures of nature as spectacle, and instead lead them to understanding their own insertion and dependence on the environment.

Frank Gohlke (U.S.A., b. 1942), Landscape, Albuquerque, 1974. Gelatin silver print.

Whereas the dominant trend of nature photography until the 1950s was one of control over nature, and the photos expressed that control in their perfect composition, symmetry, stunning visual appeal; the 1970s turn exposes a fundamental loss of control, a recognition that human activity has gone out of hand in its environmental impact, and the images show that as well in their distancing, their attention to uncanny detail, their off-balanced framing. As curator Michael Metzger, a PhD Candidate at Stanford’s Department of Art & Art History, observed in the exhibition catalogue:

“The works in this exhibition reckon with the obsolescent myths that suffuse the American landscape. Without warning we stand before them exposed — not merely to nature, but to the peculiar, precarious little concrete boxes we erect against it; to the mean, gleaming vehicles we engineer to travel through it and the traces our travels leave behind; to the next-door neighbors and the coyotes, the haze of the city, and the shadow of the mountain.”

James Alinder (U.S.A., b. 1941), Mount Rushmore (front view), South Dakota, 1973. Gelatin silver print.

One of the most interesting aspects of the exhibit is a selection of photographs from the enormous collection of photographs commissioned by the Environmental Protection Agency in the 1970s, entitled DOCUMERICA. These photographs taken by professionals and amateurs alike show various aspects of American everyday life, with an emphasis on the relationship and effect of that life to the natural environment. Many of them feature a car, as the emblematic tool by which Americans have criss-crossed the continent to enjoy its natural wonders, while destroying it slowly by emitting harmful gases. The Documerica project on its own deserves separate treatment, as a unique experiment in visual public engagement with the environment; you can now see over 15,000 of the images on the National Archives’ flickr account.

Teenager in Second Ward, Chicano Neighborhood, 1972, photography by Danny Lyon (this was one of 20,000 photos collected by the EPA between 1971 and 1978 as part of the DOCUMERICA project).

Hopefully this article convinced you that it’s worth finding your way to Cantor (entrance is free) and seeing Environmental Exposure before it is taken down.

With special thanks to Michael Metzger and Jennifer Daly.

Contact Information

Christine H. Black

Associate Director, Communications

650.725.8240

ChristineBlack@stanford.edu

Devon Ryan

Communications Manager

650.497.0444

devonr@stanford.edu

Rob Jordan

Editor / Senior Writer

650.721.1881

rjordan@stanford.edu